As Sri Lanka struggles to recover from the devastation of Cyclone Ditwah and weeks of flooding, a deeper question is emerging beneath the emergency headlines: How should Sri Lanka balance urgent rescue needs with the long-term risks of foreign-funded reconstruction?

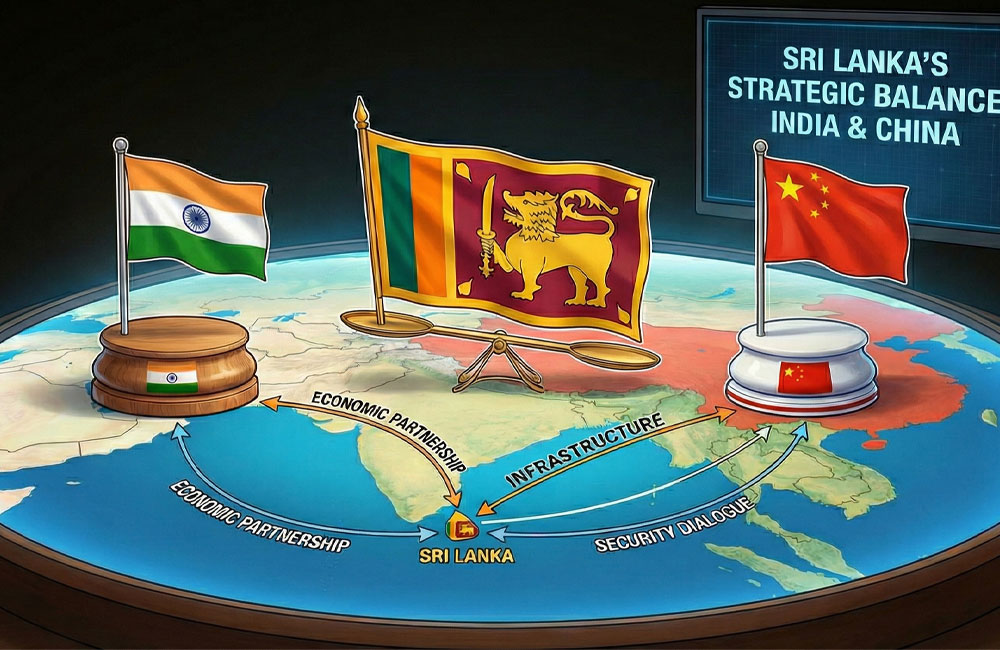

The answer is becoming inseparable from the geopolitical rivalry between India and China, the region’s two largest economic powers, both now active in Sri Lanka’s disaster response but in very different ways.

India moved with striking speed. Under Operation Sagar Bandhu, New Delhi deployed a multidimensional humanitarian package within hours, sending 53 tonnes of relief supplies, three Indian Air Force aircraft, naval vessels, specialised National Disaster Response Force (India) NDRF search-and-rescue units, and medical teams.

Helicopters airlifted stranded residents, engineers restored broken access routes, and evacuation flights repatriated more than 2,000 Indian nationals while also contributing to broader relief operations. India’s footprint is unmistakably operational: boots, machinery, helicopters, and emergency workers on the ground.

China’s engagement so far has been different in scale and style. Beijing’s immediate support included US$100,000 from the Red Cross Society of China to the Sri Lanka Red Cross, while embassy-linked community groups mobilised another LKR 10 million in donations.

Official Chinese statements indicate that further supplies and government-level assistance are “in progress” or being arranged. While not matching the rapid deployment seen from India, China’s approach fits its established pattern: financial aid first, reconstruction financing and project-based support later.

These contrasting relief models hint at a more complex reality Sri Lanka’s vulnerability is not just humanitarian, but geopolitical.

India’s swift operations reinforce its declared role as the Indian Ocean’s “first responder”, a strategic message that Colombo cannot ignore.

The tangible, highly visible nature of its assistance builds goodwill at the community level and strengthens defence and emergency cooperation. For a country still in economic recovery, Indian High Availability Disaster Recovery HADR capabilities provide immediate, lifesaving relief without adding to debt.

China’s influence, however, lies in long-term infrastructure and financing, from energy projects to major transport and port-related ventures. Beijing’s reconstruction assistance when it comes could offer scale and speed unmatched by most donors.

But these advantages come with well-known policy sensitivities: debt sustainability, project transparency, and environmental resilience. Post-disaster spending can easily become a gateway for high-cost or strategically weighted projects if oversight is weak.

This leaves Sri Lanka with a difficult but decisive task: extract benefits from both partners without deepening structural vulnerabilities.

In the immediate term, the country must continue leveraging India’s operational strength rescue teams, engineering units, medical care, and connectivity restoration because these are capabilities China does not deploy at the same pace or magnitude.

But for the reconstruction phase, Colombo must draw strict red lines: infrastructure must meet resilience standards, financing terms must be transparent, and project selection must prioritise flood protection, early warning capacity, agriculture stability, and social infrastructure.

If Sri Lanka does not set the terms, others will. The coming months will determine whether foreign financing becomes a tool for rebuilding a safer, greener nation or a new layer of long-term dependency shaped by the strategic calculus of external powers.

For a country caught between two giants, the only sustainable path is disciplined neutrality: accept the help, but guard the future.

Leave your comments

Login to post a comment

Post comment as a guest