Featured

Too Big for Our Maps, Too Small for Their Feet

Sri Lanka is one of the few countries in the world where a large, free-ranging elephant population lives in such close proximity to dense human settlement – not inside isolated reserves, but across working landscapes shaped by farming, roads, railways, irrigation systems and villages

Sri Lanka’s Endangered - A mission to save species One small step at a time

Mankind cannot survive on its own. Coexistence matters, especially with nature. In a world that continues to cut down trees, kill animals and pollute surroundings, innovative initiatives are needed to educate people on the importance of environmental conservation. Sri Lanka’s Endangered is one such project that aims to raise awareness about various endangered animals in Sri Lanka and related topics that would allow anybody who visit their website to understand their part in this conservation process.

Led by Anik Jayasekara, the team behind www.srilankasendangered.com is building a public-facing platform that connects credible environmental knowledge with everyday understanding. Built on insights from environmentalists, wildlife experts, activists and professionals in the field, each article is treated as a living piece, designed to evolve through expert insight and real-world feedback.

Anik affirms that this is not another case of overwhelming people about various environmental issues that exist in different parts of the country. But rather, a platform that allows people to read about different animals, environmental issues and understand what they could do to make a change. As a first step, the platform invites you to register if you are interested to become an advocate.

Once you register, you will receive one email every week about an animal, with related images taken by Sri Lankan wildlife photographers and “simple, expert-advised actions you can take to help.” According to the website, these articles are “short enough to read before your tea cools, but powerful enough to change how you see this island”.

The website has been designed as an interactive platform, inviting conservationists, organisations, photographers, experts, teachers, parents, volunteers and anybody interested in wildlife to contribute with their insights to continuously improve content to make it more accurate and interesting for people. The platform is also open for anybody to volunteer as a writer, accountant, translator among others to improve its outreach.

Mahendran who applied to be a Data Analyst said that the idea to help Sri Lanka’s endangered animals has never crossed his mind before. “But once I saw the volunteer post, I wanted to give it a shot. I just want to get exposed to a world where people get together and work for a good cause. I am pretty sure that one day I can go to bed thinking that, I have done my part and my best to protect the motherland and animals,” he added.

In an attempt to familiarise the concept among readers, Sri Lanka’s Endangered will publish a series of articles in the Daily Mirror fortnightly.

(Source:dailymirror.lk)

Sri Lanka’s President Speaks: Turmoil, Recovery and Diplomacy

In a candid conversation with Newsweek in the stately bilateral meeting room at the President’s Secretariat in Colombo, President Anura Kumara Dissanayake laid out the realities his nation faces in the wake of a devastating cyclone that left death and destruction in an already fragile economy.

He detailed how international partners, from regional neighbors to global powers, stepped in during the crisis, and why Colombo now sees an opening to reset ties with India, manage its complicated relationship with China and deepen engagement with the United States under President Donald Trump.

Here is a transcript of questions and answers from the interview.

Newsweek: Sri Lanka has undergone major political shifts in recent years, from protest movements to a dramatic change in the 2024 election. How do you explain the public mood that brought your government to power?

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake: The protests of 2022 were born not only from power cuts and long queues for fuel and medicine, but also from a deeper frustration with corruption, unequal opportunity and decisions made without transparency or accountability. By 2024, that public frustration had evolved into a democratic demand for a different kind of leadership. Our victory was a call for cleaner governance, economic fairness, and a break from politics as usual.

People wanted leaders who are like normal people, who would tell them the truth and accept responsibility. I see our mandate as a contract of trust—a covenant to stabilise the economy without abandoning the vulnerable, to reform institutions rather than capture them, and to prove that democracy in Sri Lanka can renew itself. We must show them that their faith was not in vain.

Newsweek: Sri Lanka sits at the crossroads of Chinese-built infrastructure, Indian regional influence and U.S. economic leverage. To what extent does Sri Lanka truly retain strategic autonomy, and how do you balance these relationships?

Dissanayake: India is Sri Lanka’s closest neighbour, separated by about 24 km of ocean. We have a civilizational connection with India. There is hardly any aspect of life in Sri Lanka that is not connected to India in some way or another. India has been the first responder whenever Sri Lanka has faced difficulty.

India is also our largest trading partner, our largest source of tourism and a significant investor in Sri Lanka. China is also a close and strategic partner. We have a long historic relationship—both at the state level and at a political party level. Our trade, investment and infrastructure partnership is very strong. The United States and Sri Lanka also have deep and multifaceted ties. The US is our largest market.

We also have shared democratic values and a commitment to a rules-based order. We don’t look at our relations with these important countries as balancing. Each of our relationships is important to us. We work with everyone, but always with a single purpose – a better world for Sri Lankans, in a better world for all.

Newsweek: How do you see President Donald Trump’s presidency changing Sri Lanka’s place in the changing world order?

Dissanayake: For Sri Lanka, success means market access and renewed investment flows. We are engaging with President Trump’s administration to position Sri Lanka as a stable and reliable partner and an Indian Ocean hub.

Newsweek: What exactly does Sri Lanka want from Washington, and what is it willing to deliver in return?

Dissanayake: Market access for our exports, particularly textiles and value-added products. We also need climate finance – we just lost several billions of dollars due to Cyclone Ditwah. It will take us a few weeks to assess the actual damage. We need grants for climate adaptation: early warning systems, resilient infrastructure, coastal protection. We need technology and investments – we want US companies to invest in Sri Lanka in all possible sectors including digital infrastructure, manufacturing and renewable energy.

We need technology transfer. What we offer is a strategically placed, stable, democratic partner in the Indo-Pacific. We are committed to freedom of navigation. We are keen on port and logistics collaboration. We also look forward to deepening cooperation on shared concerns like maritime security collaboration, counter-terrorism and drug trafficking.

Newsweek: With public debt still hovering above 100% of GDP, how do you plan to address this and avoid another default while avoiding pain for the poorest?

Dissanayake: We just completed a historic debt restructuring process, only to face yet another disaster – Cyclone Ditwah. Initial estimates indicate that the damage may well be beyond any natural disaster that our island has endured. So we will have to service debt while simultaneously rebuilding from climate disasters. This is why debt sustainability frameworks for climate-vulnerable countries must change.

We are pursuing export-led growth to tackle decades-long weaknesses in our economy. We are increasing government revenue, broadening our tax base through digitalization and protecting social spending. Over 20,000 people lost their homes in Cyclone Ditwah. We cannot impose austerity on people who have lost everything. We are expanding targeted cash transfers, subsidizing essential medicine, investing in agricultural recovery and rebuilding homes, schools, hospitals and public infrastructure. We have to do this while operating within the IMF programme parameters. We need support from our partners and international organisations.

Newsweek: Sri Lanka posted 5% growth in 2024 and is targeting a 2.3% primary surplus in 2025. Within the IMF framework, what policy levers can deliver visible relief to low-income families in the next 12–18 months?

Dissanayake: Cyclone Ditwah just battered nearly two million people, with approximately 55,000 houses damaged and some completely destroyed. These families need immediate, visible relief. One – we will have to help build flood-resistant homes. This will create construction jobs while protecting families. Two – we lost about 273,000 acres of rice paddies. We have to provide seeds, equipment and technical support so that farmers can replant. We will need a lot of funding just for agriculture restoration. This is not just disaster recovery but food security as well. Third – we are maintaining subsidies where they matter most to poor families: medicine, fuel, basic food items. Fourth – infrastructure repair will create jobs.

Newsweek: Your government has recently subjected large-scale foreign investment proposals to fresh scrutiny. How will Sri Lanka convince foreign investors that it is a predictable place to commit capital?

Dissanayake: We are establishing transparent, rules-based evaluation with clear criteria: environmental and climate resilience standards, economic viability, technology transfer and local capacity building, labour and social protection, and alignment with national development goals. Foreign investors want three things: clarity, consistency and confidence. We are creating a clean, predictable investment environment that protects both the investor and the interests of the Sri Lankan people. First, we have introduced a single-window investment approval system to reduce delays, eliminate hidden influence and provide a clear decision pathway.

Investors will be able to see the full process online, including timeframes, required documentation and responsible officials. In addition, we are drafting a new Investment Protection Act to guarantee fairness, legal certainty and enforceable rights for investors. Second, every large project will undergo transparent, rule-based evaluation. That means standardized tender procedures and pre-defined sustainability criteria. There will be no special treatment for insiders or politically connected groups, which is exactly what investors have long requested. Third, we are strengthening the legal and regulatory framework. Digital procurement systems, enforcing mandatory asset declarations and establishing independent oversight mechanisms are just a few of the measures we’re taking.

This ensures that approvals are made on merit, feasibility and national benefit, not personal networks. Finally, we are maintaining political stability and rule of law—the two strongest signals for investor confidence. A stable government aligned with long-term economic planning is far more attractive than a system with sudden policy changes or opaque decision-making. In short: Sri Lanka welcomes investment, but we want investment that is transparent, predictable and productive. When investors know the rules and trust that the rules will not suddenly change, they commit more capital, bring technology and create jobs. That is the environment we are building.

Newsweek: Given China’s long-term leases over Hambantota and Port City, do you see these as strategic risks Sri Lanka must manage?

Dissanayake: These projects are realities that we must manage intelligently. The Hambantota Port operates transparently, like any other port terminal in Sri Lanka. Our Navy and customs are in control. It serves Sri Lanka’s economic interests through job creation and regional development and doesn’t compromise our security. The lease is commercial, not military. We have been clear that no foreign military bases are permitted and we enforce it. Port City is primarily a commercial development. It will create jobs, attract investment and generate revenue. We have to monitor operations, ensure compliance with Sri Lankan law and maintain sovereignty over how these assets are used. The projects are realities that we must manage with a clear-eyed assessment of Sri Lanka’s interests—what serves Sri Lanka’s development. The recent floods and cyclone showed Sri Lanka remains unprepared for extreme weather.

Newsweek: How do you respond to criticisms of the government’s handling of the disaster?

Dissanayake: Cyclone Ditwah was catastrophic—lives lost, villages submerged, infrastructure torn apart. Response was rapid, with our forces and local authorities mobilised. Our partners stepped in as well. Although the priority at the moment is to work together and ensure Sri Lanka gets back on its feet, we need meaningful criticism to guide us. Longstanding weaknesses were visible in local preparedness, land-use enforcement and speed of relief delivery.

We are in government and we want to fix the problems. We have launched a comprehensive review of our disaster management systems. Sri Lanka’s pre-monitoring and early-warning systems must improve—especially real-time weather tracking and community alert mechanisms. We have established emergency operations centres in every affected district, deployed all available military and police resources for rescue and relief, and coordinated with international partners who responded rapidly.

We are creating a National Disaster Management Authority with real resources and authority. We will improve our forecasting through better radar coverage. We are pre-positioning rescue equipment and supplies in high-risk areas. We are mapping landslide-prone areas in the central highlands. Of course these districts have experienced landslides before. With climate change, destruction of this scale should have been expected in time. But for years and years Sri Lanka has failed to prepare adequately.

At least now, our government will work with all partners to put effective, efficient and accountable systems in place. We will rebuild Sri Lanka, better than it was before.

Newsweek: Is Sri Lanka trapped in a model where climate shocks keep setting the country back for years? What’s your long-term plan?

Dissanayake: We will be trapped if we don’t act now. This trap is not of our own making. Sri Lanka contributes negligibly to global emissions. But we face existential climate shocks that can destroy years of development progress overnight. But we must break this cycle. We can’t have every flood, every cyclone, every drought set us back to where we started. So we urge our partners to help us build an escape plan to get out of the trap.

Help us build climate-resilient infrastructure. This will cost more upfront but will save us from repeated reconstruction. Help us diversify our economy away from climate-vulnerable sectors to sectors like the digital economy, IT services, light manufacturing and climate-resilient industries. Share technology so that communities have time to evacuate and protect assets before disasters strike. Help us build natural climate-change mitigation infrastructure – mangrove restoration, reforestation and wetland conservation.

Newsweek: Who were the most reliable partners in the disaster response, and which countries will be indispensable to Sri Lanka’s future?

Dissanayake: So many countries came forward to support us. India responded the quickest with Operation Sagar Bandhu. They deployed aircraft, helicopters, naval vessels including aircraft carrier INS Vikrant, and National Disaster Response Force personnel. Our neighbours Pakistan and Maldives also provided invaluable support. We deeply appreciate their solidarity, as well as the solidarity extended to us by all our neighbours. We also remain deeply grateful to all other countries, international partners and individuals around the world who reached out and contributed. We will work with all partners – bilateral and multilateral – for infrastructure and economic development, and climate adaptation and technology. The honest answer is – we can’t afford to be dependent on any single partner. Our future depends on building and maintaining productive relationships with all partners who contribute to our nation’s sustainable development, growth and prosperity.

Newsweek: Sri Lanka retains sweeping powers under laws like the Prevention of Terrorism Act and restrictive online-safety legislation. What is your plan for these laws?

Dissanayake: These laws have been used as tools of repression. They are out of place in a democracy. We are committed to comprehensive reform. On the PTA, we are committed to repealing and replacing it with legislation that balances legitimate security concerns with civil liberties. This means ending indefinite detention, establishing judicial oversight for all detentions, protecting the right to legal counsel, and ensuring that anti-terrorism legislation meets international human rights standards. We are revising the Online Safety Act to protect free expression while addressing genuine harms like hate speech that incites violence and child exploitation.

The focus is to prevent real harm and not silence criticism. We want to work with civil society, international human rights experts and affected communities to draft replacement legislation. Bad laws rushed through will create new problems—we have experienced this in the past. Trust in government, both nationally and internationally, requires these reforms. We will act. And act soon.

Newsweek: How can rights-conscious partners trust Sri Lanka when its security laws resemble those of an illiberal state?

Dissanayake: Trust is earned through action. We have inherited what previous governments did. Changing that takes time. Rights-conscious partners should look at our actions – we are releasing political prisoners systematically, reviewing cases where people were detained under repressive laws without proper process, allowing space for peaceful protests and strengthening independent institutions – the judiciary, human rights commission, anti-corruption agencies. We are providing resources needed by these institutions and we are in the process of repealing and amending repressive laws. We are trying to dismantle systems that have been built over decades.

The political culture of control and institutional habits don’t change overnight. It requires sustained effort. Our partners should see whether we are moving in the right direction and whether our reforms are substantive. Also, whether we are backsliding or advancing. They should help us build accountable and rights-based systems. We are serious about building a rights-respecting democracy, and we urge everyone to support the process.

Newsweek: The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights recommended a dedicated judicial mechanism with an independent special counsel. How are you responding?

Dissanayake: Transitional justice for past rights violations is complex. Families deserve truth, accountability, justice and reparations. The nation requires reconciliation. We support accountability for past violations through a Sri Lankan-led process. We are currently working with victims’ groups, civil society organisations, local experts and international experts on what a credible domestic process should be.

Newsweek: Critics say the arrest of former president Ranil Wickremesinghe was politically motivated and no real steps are being taken against entrenched corruption. How do you respond?

Dissanayake: Corruption investigations must be evidence-based and not politically motivated. If the evidence warrants prosecution, political status should not provide immunity. There should be no political interference in such matters. Whether Mr. Wickremesinghe’s arrest is justified depends on evidence, and that should be tested in court through proper process—not the media or political pressure.

On institutional corruption more broadly – yes, it seems as if we haven’t done enough yet. The reason it seems that way is because corruption is deeply entrenched in institutions, built over decades. This means that putting things right requires systemic change, not just arrests. We are strengthening anti-corruption agencies. The Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption needs independence, resources and political backing. We are establishing transparency in procurement. Government contracts, particularly large infrastructure projects, must go through transparent, competitive processes.

We are digitalizing procurement to reduce opportunities for bribery. We are strengthening asset declaration and conflict-of-interest rules. We are pursuing major cases. We are establishing institutional reform that prevents future corruption and we are committed to creating a culture of accountability. We believe that credibility comes from process, not personalities. Justice in Sri Lanka must be governed by facts, evidence and due process—and that is exactly how we are operating.

We have also launched a five-year anti-corruption plan to strengthen these mechanisms, ensure continuity and make accountability a permanent feature of governance.

Newsweek: Over 300,000 Sri Lankans left for foreign employment in 2024. Youth joblessness is still above 20%. What reforms will convince a talented 25-year-old to stay?

Dissanayake: We must create a country where young people see a bright future full of opportunities, and this requires fundamental reform. In brief – meritocracy over connections; an entrepreneurship-friendly environment; competitive salaries and opportunities; quality education and skills training; pathways for returnees; livable cities and quality of life; climate resilience. We also want to create the regulatory frameworks and international partnerships necessary so that Sri Lanka’s economy is linked seamlessly with the global economy. This will expand the horizons of our people. The hard truth, however, is that even with all these reforms, some will still leave.

This is the reality in a globalized world. What we can do—and what we are committed to doing—is to create enough opportunities so that staying is a competitive choice and not a sacrifice. We also want to maintain strong connections with the Sri Lankan diaspora so that they contribute to Sri Lanka’s development and growth. A talented 25-year-old should stay because they believe they can build a successful career in Sri Lanka and contribute meaningfully to the country’s progress. That is what we are working to create—a stable, peaceful, reconciled and prosperous Sri Lanka where everyone can thrive.

Newsweek: Do you think you can “overcome” everything bad that happened in your country’s past?

Dissanayake: No. It is important to be honest. You can’t overcome the loss of thousands of lives in conflict. You can’t overcome disappearances, torture, trauma of families and events in the past that scarred generations. You can’t overcome the suffering incurred by economic mismanagement and collapse. You can’t overcome death and tragedy. What we can do, and what we must do, is to ensure that these horrors that happened in the past do not recur. That they are never repeated. The pain of people who lost loved ones will not disappear just because there is a new government or a new law.

The best we can do is acknowledge that pain exists and ensure that it wasn’t in vain by making sure that things like this don’t happen again. Overcoming suggests that we can move past and forget. We can’t erase the past. We can’t forget the past. We have to acknowledge the past and make those memories and painful experiences drive us to ensure non-recurrence and build a better, more inclusive nation. The question, to my mind, is not whether we can overcome something bad but whether we can break the cycles that produced those painful experiences. Whether we can build institutions that protect everyone regardless of ethnicity, language or religion.

Can we ensure that political differences don’t lead to violence? Can we create a country where citizenship is equal and all communities feel that they belong equally? Can we create a country with strong institutions where everyone is accountable? I think that this is achievable. But it requires facing the past honestly, and not pretending to overcome it. It requires constitutional reform that protects minority rights and ensures equal citizenship. It requires empowering communities and protecting the vulnerable. It requires economic opportunity for all; it requires dignity for all.

We can’t overcome the past, but we can refuse to repeat the bad things by learning from the past and reforming so they don’t get passed on to future generations.

Newsweek: What is Sri Lanka’s biggest challenge right now?

Dissanayake: Our biggest challenge is achieving sustainable and equitable development while dealing with overlapping crises. We just completed historic debt restructuring – $25 billion restructured, $3 billion forgiven. But now we are confronted with a crisis beyond our control—Cyclone Ditwah has made our challenges even bigger. It’s almost as if when we are taking two steps forward, something beyond our control has pushed us back three steps. Yet our people have extraordinary resilience. Our debt is above 100% of GDP.

Although we managed to recover from the economic crisis, our economy is still fragile, and now over a million people have just been affected by disaster, and they need immediate support. We have to move beyond the cycle where every achievement is temporary, with some crisis setting us back by several years. I think that this is our biggest challenge. We must prove that Sri Lanka remains resilient and viable. That we can withstand climate disasters.

That we can offer young people a future worth staying for. Everything else—debt management, disaster preparedness, economic reform, youth employment, climate adaptation—flows from that central challenge: proving Sri Lanka has a sustainable future. Rebuilding confidence in our people and inspiring and motivating them to take on the responsibility of building our nation as a resilient, peaceful, reconciled and prosperous nation for all is something that I am deeply committed to.

(Source - Newsweek)

‘Alathi Amma’: Woman serving the Dalada Maligawa

Among the 423 presentations awarded for the service extended to the Dalada Maligawa during the last 15 years, only one woman received the recognition. She was ‘Alathi Amma’.

‘Alathi Amma’, enters the inner shrine room and closes the door while the services monks exit the shrine. She, sometimes with another member from the same family, does the rituals on Wednesdays, where the Sacred Tooth Relic is bathed with perfumed water, specially during annual Esala Perahera and during the exposition of the Sacred Relic.

The ritual is simple but dignified and some tend to call her as the stepmother of Buddha. What she does inside the inner shrine without the service monks, is not questioned. But the service monks are aware of the ritual and they do not speak on this ritual.

The ritualistic duties have been passed on to them over the years from generation to generation. This family is not aware of the origins of these practices. It is believed that this ritual is inherited from two Ranaweera families and has been passed on to them by their ancestors.

There are no corresponding words to describe the ritual. One sees only that these two women enter the inner shrine with a wick dipped in pure coconut oil lighted and placed on a betel leaf. They do not speak about this ritual. But the service monks knows the ritual and they too does not speak about this ritual.

During the period of late Venerable Rambukwella Vipassi Thera, who was the Mahanayake of the Malwatta chapter, this scribe wished to know the origins of this ritual, and the status symbol of these two Alathi Ammas as when they move into the inner shrine with the service monks stepping out and the doors are closed. While waiting inside the inner shrine, I took the liberty to discuss with the office of ‘Alathi Amma’ and how it came into the Sri Dalada Maligawa. I was rechecking what was told by my uncle, who was a monk and had conducted service in the inner shrine around four times.

Venerable Vipassi Thera summoned one of the Alathi Ammas in service and asked her whether she knew how they had come into service. She told the Mahanayake that this was bestowed upon them. Her reply was that it has been passed to them from the previous generation when the elders pass away. But they were unable to trace the origins.

The Mahanayake thera, in his observation, said that this could be because kings at that time were Hindu or aligned to Hinduism although they performed Buddhist religious performances, this might have become a custom. Yet, he added that this needs to be verified. The thera also attributed to the fact that Hindu kings allowed women to perform rituals for blessings to ward off evil effects, when they return to the palace after attending official functions outside the palace. The Mahanayake thera further explained that this would be the same ritual now performed for Sacred Tooth Relic. He added that there is nothing wrong in these rituals as it wishes for wellbeing of everyone.

The ritual is to say “ Ayu Bo Wewa” thrice. It is a simple yet dignified process.

(Source:dailymirror.lk)

Who cares for the poor? Your guess is as good as mine

It’s now a year since the NPP government was overwhelmingly voted into power at the 2024 general elections. The new government in the run-up to the general election promised much, but today has little to show.

With hunger and malnutrition stalking the land at the time, the NPP promised to bring down the cost of living. It described the International Monetary Fund agreement signed by past president Wickremesinghe as being one of the main causes of rampant povertyand promised to renegotiate the agreement.

One year later however, the poor continue to be poor and live in extremely distressing conditions. UNICEF in its report on Lanka for 2025 points out that approximately one in four under-five-year-olds are not growing as they should. The report adds one in six babies are born with low birth weight. The obvious conclusion is that the economic crisis has made it harder for families to access adequate healthy food.Making matters worse, today the government has gone back on its word regarding renegotiating the IMF agreement and has become one of its chief proponents. Sadly, the political opposition in parliament, rather than coming together to pressurise government to tackle this important issue, continues bickering among themselves. For opposition political parties, the main problem seems to be the question of who would lead a combined opposition –not problems faced by the people.

The health sector remains in a mess. Doctors are threatening trade union action if a solution to their problems is not proposed within 48 hours. The country faces a critical shortage of specialist doctors, with experts calling for around 4,000 specialists by 2025, while the current number is around 2,000.

Doctors also claim essential drugs are in short supply with many varieties of medicines not available at government hospitals. This is especially so in the case of cancer patients as well as those suffering heart diseases, diabetes and replacement surgeries where hospitals are faced with severe shortages.

Resultantly, patients at government hospitals are often called to purchase these necessities at their own expense from private agencies at astronomical prices.Since those seeking treatment at government hospitals are from the poorer sections of the community, they are unable to meet these costs.

If these problems are not corrected now, patients from poorer backgrounds may soon be faced with a situation where they have no alternative but ‘to simply lie down and die’.

While it could be that a few corrupt individuals are sabotaging the control, purchase and distribution of medicinal drugs, politicians in government or in the parliamentary opposition seem unable or unwilling to drop their differences to tackle these issues. Doctors themselves have become frustrated and are now threatening to take trade union action if the government does not propose a time-bound solution to problems in the health sector, as well as to salary anomalies of the doctors themselves. Teachers and school principals too, have threatened trade union action if outstanding issues faced by them are not attended to sooner rather than later.

UNICEF

UNICEF

While ‘we the people’ understand most of the problems faced by our present rulers were caused by past governments, the NPP regime cannot now try to wash its hands of past misdeeds. They too joined hands with different past regimes and are also responsible for the corruption and misrule during those days.

On the subject of corruption and misrule, however, the present NPP is living up to its word. From the highest in the land, to ex-ministers, to ex-deputy ministers and other high ranking state bureaucrats, government has let the law take its course without interference. Today, many of these individuals are either in remand custody, charged with specific crimes or languish in prison.

While the parliamentary opposition has as yet to lead demonstrations against the cost of living, lack of medicaments and malnutrition among our children, they were quick to come together against the arrest and prosecution of past political leaders. In fact, it was the arrest of immediate past president Wickremesinghe which brought the diverse parties of the opposition together, NOT the people’s plight.

Last week’s joint opposition rally at Nugegoda was a spin off from that incident and even there the main opposition groups stayed away. So who cares for the people?

Then again, a single year in power cannot solve decades of corruption, abuse and misrule.

(Source - DailyMirror)

Global Leaders Gather in Davos as WEF 2026 Seeks ‘Spirit of Dialogue’

Against one of the most complex geopolitical backdrops in decades, the World Economic Forum (WEF) has convened its 56th Annual Meeting in Davos, Switzerland, bringing together nearly 3,000 leaders from 130 countries. Held under the 2026 theme “A Spirit of Dialogue,” the summit seeks to restore cooperation at a time of deep global fragmentation and unprecedented technological change driven by artificial intelligence.

With trust in traditional multilateral institutions under sustained pressure, this year’s meeting positions Davos as a rare neutral platform for public–private collaboration. A record 400 government officials and 850 chief executives are participating, tasked with identifying practical pathways toward global economic and political stability.

What Is the World Economic Forum?

Founded in 1971 by German engineer and economist Klaus Schwab, the World Economic Forum is a non-profit international organization designed to foster cooperation between governments, businesses, and civil society. While it holds no formal political power, the WEF functions as a convening platform where policymakers and corporate leaders engage in dialogue on global challenges.

At the heart of the Forum’s mission is the concept of stakeholder capitalism—the idea that companies should serve not only shareholders, but also employees, consumers, communities, and the environment.

A High-Profile Guest List

Government participation has reached an all-time high this year, with more than 130 countries represented.

Among the political leaders attending are U.S. President Donald Trump, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen.

The technology sector is also strongly represented, particularly from the artificial intelligence frontier. Key figures include NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, and Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei.

Leaders of major international institutions—including the United Nations, International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and NATO—are also present, underscoring the Forum’s focus on global security and economic resilience.

The 2026 Agenda: Five Key Priorities

While Davos has long attracted criticism for elite networking behind closed doors, the public-facing agenda this year centers on five core challenges:

- Cooperation in a Contested World: Rebuilding dialogue and trade amid declining trust and geopolitical rivalry.

- Unlocking New Growth: Identifying economic opportunities in a high-debt, slow-growth global economy.

- Investing in People: Advancing a global “reskilling revolution” to prepare workers for an AI-driven future.

- Responsible Innovation: Ensuring generative AI is developed and deployed in ways that benefit society.

- Planetary Boundaries: Promoting a “nature-positive” economic model to address climate change and environmental degradation.

As discussions unfold in the Swiss Alps, expectations remain cautious. While the WEF cannot enforce policy, its ability to convene influential actors in one place continues to make Davos a key barometer of global priorities—and a testing ground for whether dialogue can still bridge a divided world.

Blind Party Loyalty Will Hinder Nation-Building And Prosperity

A Degree Of Complaisance And Inclusivity Will Go A Long Way

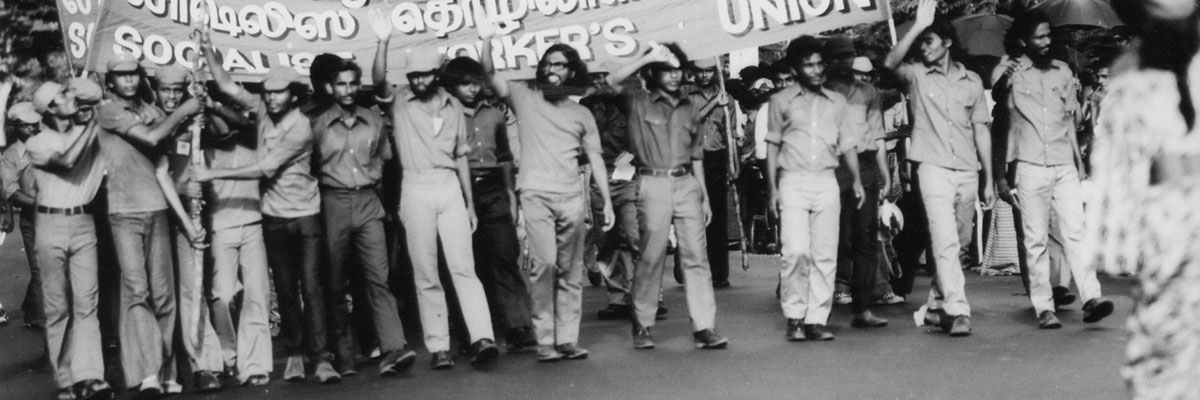

Comrade Rohana Wijeweera, the founder of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), was arrested and subsequently murdered 36 years ago on November 13. His disappearance in 1989 symbolised the turbulent end of the JVP’s second insurrection, extreme political violence involving the State, its affiliated groups, and the JVP itself. This offers us the chance to reflect on the past and the important lessons that can be learned, which will be crucial for Sri Lanka's future.

1989: A Watershed Year

The late 1980s were one of the most painful chapters in Sri Lanka’s post-independence history. The 1983 anti-Tamil riots and the 1987 Indo–Lanka Peace Accord turned the political tensions that existed into open conflict. The Accord, introduced as a peace initiative, instead triggered widespread mistrust, and heightened nationalism in the South. The JVP, operating underground as it was already proscribed, seized on these sentiments to launch its armed campaign against the State.

Both sides responded with escalating violence. Thousands of civilians, activists, and ordinary youth paid with their lives. Forced disappearances and extrajudicial killings were tragically commonplace.

The year 1989 also coincided with major global shifts. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union signified the decline of the socialist order, which had inspired many leftist movements around the world, including those in Sri Lanka. Neoliberal economic policies were rapidly expanding, reshaping international relations and national priorities.

Three and a Half Decades Later: A Changed Political Landscape

Today, Sri Lanka stands in a dramatically different political momentum. The JVP, which struggled through parliamentary democracy, has travelled a long path into mainstream politics. The National People’s Power (NPP) coalition led by the JVP achieved resounding victories in 2024, forming the government under President Anura Kumara Dissanayake.

The NPP administration has committed itself to combating corruption, controlling narcotics trafficking, and rebuilding the credibility of public institutions. Like other global movements for reform, such as the progressive shift symbolised by Zohran Mamdani’s recent mayoral win in New York, the NPP government emerged from widespread public demand for change following years of economic decline and mismanagement by previous regimes. However, gaining political power is only the first step. Transforming governance and rebuilding trust will require a sustained commitment to transparency, accountability, and social justice.

Blind Loyalty, Class Compromise, and the Social Justice Imperative

Sri Lankan politics has long struggled with the tension between blind loyalty to party, ethnicity, or faith, compromise with entrenched interests, and the quest for justice for all citizens.

Blind loyalty distorts democratic decision-making. It leaves little room for dissent or rational debate. During the Southern insurrections and the Northern conflict, loyalty to leadership, rather than to truth or humanity, justified violence and silenced differing voices. Such total and uncritical allegiance continues to threaten our institutions and civic values.

Globally, many countries struggle to separate religion from governance. With constitutional preferences granted to the majority faith, Sri Lanka—a multiethnic, multireligious society— faces the same challenge. Effective democracy requires that national policy be guided by equal citizenship, not sectarian influence.

Class compromise refers to alliances formed between leftist groups and capitalist factions. In Sri Lanka, partnerships between socialist parties and the SLFP date back to the 1950s. While such arrangements achieved short-term reforms, they also diluted transformative agendas. The global rise ofneoliberalism from the 1970s further tilted power towards capital, normalising privatisation and diminishing labour rights.

Against this backdrop, social justice seeks to remove structural barriers and guarantee equal opportunities, particularly for marginalised communities. It calls for redistributing power as well as resources — a principle increasingly central to contemporary political reform.

Learning from the Violent Past

The violent episodes of the late 1980s continue to be the most contested part of JVP history. Allegations against government death squads and armed JVP units remain unresolved, contributing to deep emotional trauma among families that had become targets of the violence.

To their credit, in 2014, the JVP publicly acknowledged its role in the conflict and expressed regret for the suffering caused (https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c206l7pz5v1o). This was an important moral step toward national reconciliation. When the JVP returned to democratic politics in the 1990s, it was perceived as a sign of its readiness to participate in institutional procedures and nonviolent discourse.

Electoral success followed — especially in the 2004 parliamentary polls, where the JVP entered government as part of the United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA). This participation provided governance experience yet also raised internal debates about ideological consistency and coalition politics.

Economic Challenges and Public Expectations

Following the 2022 Aragalaya protests, public confidence in political elites plummeted. The eventual ascent of the NPP reflected broad frustration with corruption and economic instability. Inheriting a fragile economy, the new government must now balance fiscal constraints while protecting vulnerable communities.

Despite early criticism, the administration has worked within the IMF programme to achieve stabilisation, while also signalling greater safeguards for social welfare. The 2025 budget introduced measures aimed at supporting low-income families, promoting local industry, and restoring economic growth.

Success, however, will rely on visible results, particularly in reducing poverty, supporting small and medium enterprises, and strengthening agricultural and employment opportunities.

Towards Wider Inclusivity

The NPP’s electoral coalition brought together youth, workers, and professionals from diverse regional and ethnic backgrounds. It demonstrated that politics in Sri Lanka can transcend traditional divides.

Yet, much more must be done. The concerns of Tamil and Muslim communities, including language rights, land issues, and political representation, remain unresolved. A firm and fair commitment to meaningful devolution is essential.

Sri Lanka’s dependence on a majoritarian model of governance has increased mistrust and fueled decades of conflict. In contrast, global examples show alternative approaches. For instance, Belgium has achieved equality between its Dutch and French-speaking populations through a system of constitutional power-sharing. This power-sharing has strengthened national unity rather than undermining it.

The government’s recent commitment to allocating funds for Provincial Council elections is a positive signal. A clear roadmap for fully implementing the 13th Amendment would reaffirm Sri Lanka’s commitment to pluralism and reconciliation and reap the benefits of participatory democracy for our multi-ethnic land.

Responsible Governance: Evidence Over Emotion

The central message from the upheavals of our recent past is simple: democracy cannot rely on blind loyalty. Effective governance must be built on:

- Informed public trust

- Respect for facts and law

- Accountability for wrongdoing

- Openness to criticism

- Civic participation at all levels

Both Sri Lanka and the United States illustrate how political gains achieved through wide grassroots mobilisation must be continuously nurtured. The NPP came to power on a wave of public activism. Maintaining that engagement, especially among young citizens, will determine whether reform succeeds or stalls.

At the same time, legal and institutional reforms must be seen to deliver justice. While anti-corruption and anti-narcotics measures are underway, delays in holding offenders accountable may erode trust. People need to see that the law applies equally to all.

And above all, governance must remain focused on easing the daily burdens of citizens: cost of living pressures, unemployment, healthcare, and education. Economic stability and social dignity must progress hand in hand.

Conclusion: A Future Built on Critical Thought

As we remember the harrowing events of November 1989, we are reminded that political violence and blind allegiance brought only divisions and tragedies. The responsibility of this generation, and its elected representatives, is to ensure such mistakes are never repeated.

Sri Lanka’s path forward hence requires:

- Critical thinking over unquestioning obedience

- Democratic debate over emotional polarisation

- Integrity over expediency

- Unity in diversity over majoritarian dominance

From the beginning, many JVP members and supporters believed that following orders without questioning was the only way to realise their goals. Nevertheless, that obedience can be attributed to the blind loyalty that unconditionally supported the unprincipled deviations from a left perspective, which ultimately led to devastating consequences.

A lack of democratic debate allowed the formation of groups within the JVP and caused the party to split more than once. Factions appear to have been unwilling to reach a consensus when their political perspectives were not always congruent. But throughout its existence, the JVP had, for the most part, reached decisions through unanimity.

Given that they have been elected to power, the NPP must take these issues more seriously. To prevent emotional polarisation, which will ultimately weaken or paralyse it as a political entity, democratic debate should be permitted, and critical thinking should be encouraged in the development of its policies to arrive at programmatic positions.

The JVP's transformation into a governing force serves as an illustration that societies can progress beyond their conflicts. The challenge now is to create a political culture where trust is earned through transparent actions and not demanded through loyalty.

If Sri Lanka can develop an inclusive and mature democracy that respects all of its citizens and honestly learns from its past, those painful memories will serve the noble purpose of guiding us toward a just and peaceful tomorrow.

Lionel Bopage

AKD rejects another economic crisis while Rajapaksas blamed for dismantling key ministry on disasters

Despite Cyclone Ditwah’s departure from the country after causing much destruction to human lives and property weeks ago, Sri Lanka continues to be in the eye of a socioeconomic and political storm in Ditwah’s aftermath. President Anura Kumara Dissanayake (AKD) seems to be shouldering the heavy burden of rebuilding the country, with a majority of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP)-led National People’s Power (NPP) Government engaged in verbal clashes with members of the Opposition.

The arduous and mostly costly task of rebuilding the country following the recent disaster is expected to take time, with even senior Government members stating that it will take close to two years for the completion of the complete rebuilding programme. While a final estimation of the total damage caused and the cost for rebuilding is yet to be announced, officials believe that the cost could amount to around $ 7–8 billion.

However, the announcement by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on Friday (19) evening that its Executive Board had approved emergency financing for Sri Lanka under the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI) that would provide the country with around $ 206 million undoubtedly provided some reprieve to President AKD and his Government.

Meanwhile, persons affected by the disaster as well as Opposition politicians continue to point out to the Government the delay in distributing the cash grants that were announced by the President on 5 December in Parliament.

Responding to these statements, Public Security Minister Ananda Wijepala told Parliament last week that the initial grant of Rs. 25,000 paid for flood-affected families to clean their houses had so far been distributed among 257,000 families out of the total of 493,000 entitled to the payment. He also stated that out of the 610,000 families affected by the cyclone, 493,000 families were eligible to receive the initial grant of Rs. 25,000 and that Rs. 6.4 billion had been paid out of the total allocation of Rs. 17.6 billion.

The President last week also outlined more relief packages to businesses that were affected by the recent cyclone. He also rejected claims that the proposed Rs. 500 billion supplementary allocation would lead to national bankruptcy by April 2026.

President AKD noted in Parliament on Friday (19), at the conclusion of the debate on the Rs. 500 billion supplementary estimate that was presented to Parliament, that Sri Lanka would use a Rs. 1,200 billion cash buffer in the Treasury for cyclone relief and recovery.

“For a long time, the Treasury account was in overdraft. In 2018, it was Rs. 180 billion, in 2019 Rs. 244 billion, in 2020 Rs. 575 billion, and in 2021 it rose to Rs. 821 billion,” the President said. “In contrast, by November 2025, under our Government, the Treasury account showed a positive balance of Rs. 1,202 billion – a Rs. 2 trillion improvement,” he said.

“If we did not have the cash buffer we would have had to look for other ways to finance the spending,” he added.

AKD firmly dismissed claims by some members of the Opposition that the relief package announced by the Government would result in the country being pulled back into another economic crisis by April next year. He explained that the decisions regarding Government expenditure were being made after cautious consideration.

Seeking a PSC

Meanwhile, a group of Opposition Members of Parliament (MPs) handed over a letter to the Speaker of Parliament to appoint a Parliamentary Select Committee (PSC) to probe the reason for the delay by relevant authorities in communicating to the public regarding the cyclone that hit the country late last month and the allegation that early warnings by the relevant State institutions had not been heeded by the authorities.

Led by Opposition Leader Sajith Premadasa, the Opposition MPs had noted in the proposal that weather warnings had been issued in advance by the Department of Meteorology and international media outlets, with interpretations made available prior to landfall, and that despite this, relevant authorities had failed to take adequate preparatory measures.

The MPs had stated that this lack of preparedness was deeply regrettable and asserted that many lives could have been saved if timely action had been taken. They had also drawn parallels to past crises – the Easter Sunday attacks and the economic collapse – during which special parliamentary committees were appointed.

The proposal had also requested that the committee consist of 30 members, with proportional representation from both Government and Opposition parties, and include members from all 22 districts affected by the cyclone.

Scrapping a key ministry

While the Opposition sought the appointment of a PSC to probe the failures during the recent disaster, the Frontline Socialist Party (FSP), a splinter group of the JVP, made some interesting revelations last week.

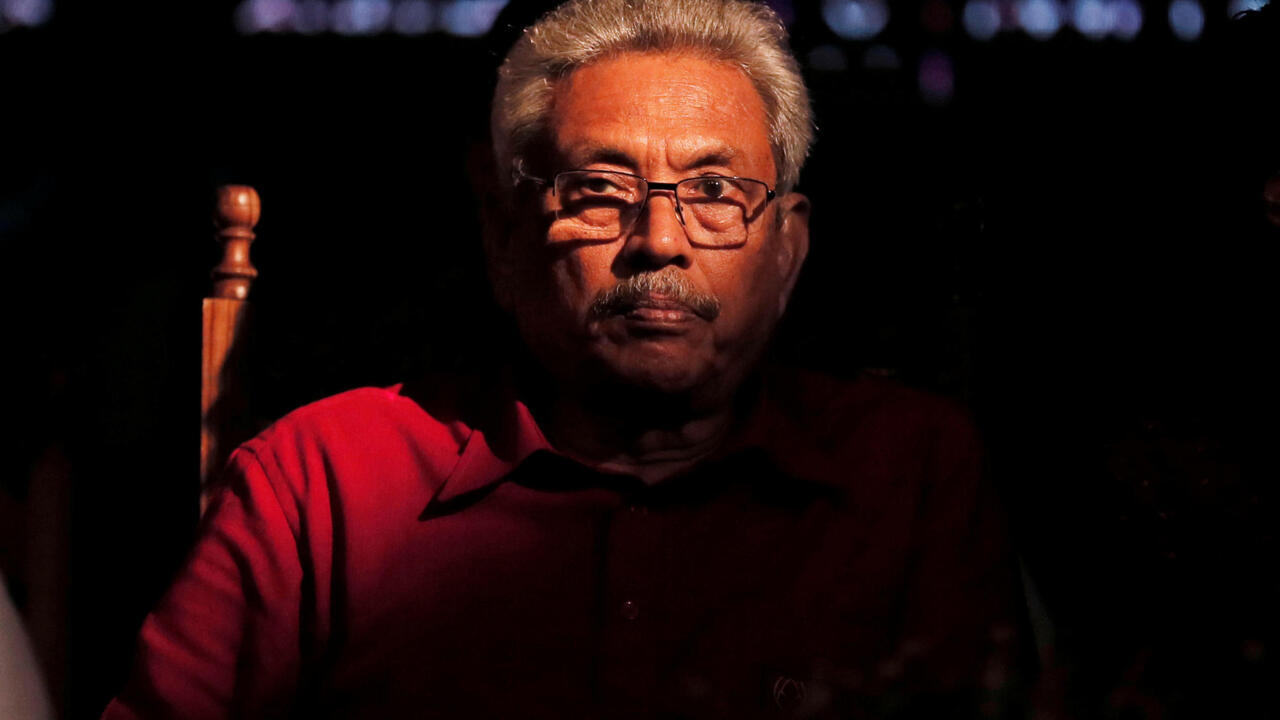

FSP Politburo member Pubudu Jayagoda claimed that the Disaster Management Ministry, which is a key ministry, had been scrapped in 2020 during President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s (GR) presidency. He explained that GR had not included a Disaster Management Ministry in his Cabinet and had taken steps to assign the Disaster Management Centre (DMC), Meteorology Department, National Building Research Organisation (NBRO), and other institutions relevant for managing disasters under the Defence Ministry and the military.

The scrapping of the Disaster Management Ministry was therefore deemed to be the main reason for the failure to have a centralised mechanism to address disaster situations. “It is this reason that had caused the failure to activate the centralised operations system that earlier operated on early warnings issued by the relevant departments,” Jayagoda explained, adding that GR had believed that the military was efficient enough to handle disasters as well.

A highly-placed source noted that once the ministry had been done away with and the institutions had been assigned to the Defence Ministry to operate mostly under military purview, there had been no proper reviews of the systems within the disaster preparedness and mitigation apparatus to be on par with global technological advancements.

Jayagoda claimed that some members of the Opposition, especially the Rajapaksas and the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP), should understand that they were the cause of this disaster since they were responsible for dismantling the system to prepare and mitigate disasters.

Once the ministry was done away under GR’s Government, the Ranil Wickremesinghe Government had also followed the same path as GR. However, the fault of the incumbent JVP/NPP Government is that it had followed the path set by GR and continued by Wickremesinghe without realising the importance of a Disaster Management Ministry, especially given the increasing impact of climate risks.

Harini rejects ex-Presidents

Meanwhile, a statement made by Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya in Parliament on Friday (19) that the Government would not seek the support of former leaders who were involved in corruption through disasters in raising funds to rebuild the country following the recent disaster gathered criticism from Opposition parties. Several members of the Opposition claimed that the Government was agreeable to accept millions given by a former President but continued to insult them afterwards.

Amarasuriya had noted that the people and international communities had offered to support Sri Lanka due to the trust placed in the good governance practices of the incumbent Government and that it was better not to involve leaders who had lost public trust.

The Prime Minister had made these remarks in response to a statement by Opposition MP Rauff Hakeem that the Government must seek the support of former Presidents in appealing for international support in the recovery effort.

JVP General Secretary Tilvin Silva meanwhile had also made a similar statement while explaining the reason for the inflow of foreign assistance to aid in relief and rehabilitation work following the recent cyclone. He has said that foreign assistance was flowing in because of the international community’s firm belief that the JVP/NPP Government did not swindle funds.

According to him, assistance is flowing in significantly from other countries for the people affected by the natural disaster and aid will continue to flow in.

TPA writes to AKD

Meanwhile, Tamil Progressive Alliance (TPA) Leader Mano Ganesan has written to President AKD requesting a meeting to discuss the challenges faced by the Malaiyaha (up-country) community following Cyclone Ditwah.

Ganesan has noted: “At the outset, we wish to acknowledge and appreciate your decisive leadership during this exceptionally challenging period of national crisis.”

He has further stated that residents of the hill country, particularly the Districts of Kandy, Nuwara Eliya, Badulla, and Matale, as well as the surrounding areas, have been among the worst affected by the recent Ditwah disaster.

“The Malaiyaha community, which continues to register comparatively low and, in some sectors, negative human development indicators – especially in land ownership, housing, education, health, and poverty alleviation – requires a differentiated and targeted approach in the recovery and speeding up rebuilding phase.

“In this context, we respectfully request an urgent meeting with you involving political and civil representatives of the Malaiyaha community to deliberate on a coordinated and sustainable framework to address these unique challenges,” Ganesan has added.

Udaya accuses AKD

Former Minister Udaya Gammanpila meanwhile has accused President AKD of criminal negligence over the recent disaster that claimed hundreds of lives and has threatened to pursue legal action once the President leaves office.

Gammanpila has claimed before the media that criminal charges will be filed against AKD after he completes his presidential term in 2029. “When you step down from the presidency in 2029, we will file criminal negligence cases against you without fail,” the former Minister has said, adding that evidence had already been gathered to support the allegations.

According to Gammanpila, the maximum penalty under the law for such an offence is five years’ imprisonment.

Harin’s prediction

Meanwhile, United National Party (UNP) Deputy General Secretary Harin Fernando, who stirred the pot at last month’s joint Opposition rally in Nugegoda by referring to the SLPP’s Namal Rajapaksa as the ‘Prince of the Stage,’ has this time around predicted yet another economic crisis in the country by April next year. He noted that Sri Lanka could face a major economic crisis by April 2026 if the fallout from the Cyclone Ditwah disaster was not managed properly.

“If there is no proper plan, programme, or projection, Sri Lanka will move towards a massive economic collapse by the Sinhala and Tamil New Year,” Fernando claimed at a media briefing in Colombo on Monday (15), adding: “Write down today’s date. We warned you.”

He further warned that it would be important to look at the positioning of the US Dollar against the Sri Lankan Rupee by 15 April and “look at what kind of economic contraction the country will face. I do not want that to happen, but it will if this situation is not managed properly.”

Losing LG budgets

Meanwhile, the ruling JVP/NPP that controls the Galle Municipal Council, which is one of the key Local Government (LG) bodies in the Southern Province, witnessed the defeat of its maiden budget on Monday (15) by two votes. The 36-member council had recorded 17 votes in favour of the budget and 19 votes against it.

The Opposition had objected to the 2026 budget presented by the ruling party, stating that there was not much of a difference between the latest proposals and those presented in last year’s budget.

Opposition councillors in the council had blown red balloons and burst them as a mark of protest while voting against the budget.

The JVP/NPP also lost the inaugural 2026 budget of the Balapitiya Pradeshiya Sabha on Tuesday (16). The budget was rejected by a narrow margin of one vote, with 17 councillors voting against it and 16 voting in favour.

Meanwhile, the JVP/NPP’s 2026 budgets were defeated in the Peliyagoda Urban Council and the Ratnapura Municipal Council. In Peliyagoda, eight JVP/NPP councillors had voted in favour of the budget while nine councillors representing all parties in the Opposition had voted against. In Ratnapura, the JVP/NPP’s budget had received 13 votes in favour and 14 votes against.

NPP MP criticises Minister

Meanwhile, trouble faced by the ruling JVP/NPP seems to now go beyond the defeats experienced by the party at many Local Government bodies, with an incident recently being reported of a ruling party MP criticising a Minister of the Government led by his own party.

The incident had taken place when JVP/NPP Kurunegala District MP Dharmapriya Dissanayake had criticised the conduct of the Trade Ministry under the purview of Minister Wasantha Samarasinghe over the destruction of a State-owned building in the Kurunegala area. He has noted that the destruction of the building had been carried out on land belonging to the Trade Ministry without any form of coordination. “This is just crazy. Although I’m an MP of the governing party, these incidents should not be allowed,” the MP has stated.

Dissanayake has claimed that he opposed the actions of the ministry since he did not approve of the destruction of State-owned buildings, especially without the knowledge of the divisional or district secretaries or even the grama niladhari. A video clip posted on social media shows him explaining the destruction caused to the building and even taking a telephone call to an official in a State institution under Samarasinghe’s purview.

The de facto magistrate

While a JVP/NPP MP openly opposed and criticised the conduct of Minister Samarasinghe’s ministry, the ruling party’s Mayor of the Kaduwela Municipal Council Ranjan Jayalal seems to have assumed the role of de facto magistrate.

An audio recording of a person said to be Jayalal reprimanding a group of individuals including a lawyer who had met him to discuss some issues, claiming he was the Mayor and that he therefore possessed the powers of a magistrate, was shared on social media last Wednesday (17). The voice said to be of Jayalal is heard stating that no one can try to intimidate him since he is the de facto magistrate as the Mayor.

In the recording, it is also heard how the individuals who had arrived at the Mayor’s Office to resolve some issues are shouted at and chased out by the voice said to be Jayalal’s.

The Bar Association of Sri Lanka (BASL) meanwhile has issued a statement condemning Jayalal’s conduct, especially the way he had addressed a lawyer, and has urged the President to take action against the member of his party.

PSC for PCs

Amidst these developments, the Government continues to face pressure on holding the delayed Provincial Council (PC) Elections, especially with Opposition parties continuing to claim that the ruling party is delaying the polls due to the knowledge that it would be defeated when the elections are held.

However, it is learnt that the Government is looking at a proposal that has been submitted by the ruling party to appoint a PSC to study and make recommendations to the House on amendments required to be made to the electoral system for Provincial Councils in order to enable the holding of the delayed polls to the provinces.

The proposal presented by the Leader of the House has reportedly been included in the new Order Book that has been prepared following the conclusion of the Budget process.

The proposal has also stated that there needs to be a broader and in-depth discussion on the country’s electoral system and that this discussion should include topics like making female representation compulsory, youth representation, campaign finance limits, a mixed electoral system of first-past-the-post and proportional representation, the ability to cast early votes, and ensuring voting rights of migrant workers.

The report of the PSC is expected in three months from the first meeting of the committee or at the end of an extension period if such is granted by the House.

Addressing Parliament last week, Prime Minister Amarasuriya reiterated the Government’s commitment to hold the PC Elections as soon as the legal impediments to holding the polls were cleared, adding that the Government had already taken measures to allocate the necessary funds to hold the polls in next year’s Budget.

“The inability to hold PC Elections thus far is due to the fact that the delimitation process required under the provisions of the Provincial Councils Elections (Amendment) Act No.17 dated 2017 has not yet been completed. Accordingly, a study is currently being conducted to determine whether the elections should be held after completing the delimitation process, or whether amendments should be introduced to the provisions of Act No.17 of 2017 in order to proceed with the elections,” she said.

SJB proposal

While the Government talks of holding the delayed PC Polls next year, Opposition parties are continuing to explore the possibilities of forming broader alliances. The Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) and the UNP are two of the main Opposition parties that are looking at forming an alliance by first working on a common work plan.

A team led by UNP Deputy Leader Ruwan Wijewardene was appointed by the UNP side to discuss an initial agreement between the two parties.

However, it is learnt that the SJB side has continuously called for an alliance between the two parties under a leadership other than that of UNP Leader, former President Ranil Wickremesinghe. When both parties, the SJB and UNP, decided to officially discuss entering a common work programme, SJB seniors had urged SJB Leader Premadasa that the leadership of an alliance with the UNP should be held by him (Premadasa) and that the UNP side in the new endeavour should be led by a party senior other than Wickremesinghe.

It is learnt that the SJB side has already communicated to the UNP side that an alliance between the SJB and UNP should be led by the SJB Leader since the party is the main Opposition in Parliament. In the event the two parties form an alliance under Premadasa’s leadership, Wickremesinghe would then have to resign from the UNP leadership and be appointed to a senior post like senior adviser or senior patron.

RW’s response

It is in such a backdrop that Wickremesinghe had stated last week at the UNP Management Committee meeting held at the Party Headquarters, Sirikotha, that he was prepared to step down from the party leadership to make way for the SJB-UNP alliance.

During the meeting, Wickremesinghe had asked for a progress report on the talks between the UNP and SJB, saying that he had not yet received an official report on the talks. He had also stressed to the Executive Committee that the discussions must be concluded swiftly as there was no time to waste, since from next year Opposition parties should unite to build a strong people’s force against the Government.

Wickremesinghe had then urged that the ongoing talks be expedited.

When the former President had been informed of the SJB’s proposals, he had told the committee that if a consensus was reached between the UNP and SJB to merge, and if the UNP Executive Committee proposed that Premadasa or another individual should take over leadership, he would have no objection since he supported the merger of the two parties.

“I have been the Party Leader for a long time. I became the country’s President. I have reached the highest position possible. At the most difficult moment for the country, I took responsibility and worked to lift it up. Therefore, stepping aside is not a problem for me. But this must be concluded quickly,” Wickremesinghe was quoted as telling the committee in media reports.

Soon after the meeting, pro-Wickremesinghe groups started to inform the media of Wickremesinghe’s preparedness to step down from the party leadership.

No takers

However, those who are well aware of Wickremesinghe’s antics know very well how he operates. This is not the first time he has expressed preparedness to step down from the party leadership.

Whenever there has been any dissension growing within the UNP in the past and currently as seen in the push for the UNP to align with the SJB as well as for a change in leadership, Wickremesinghe has stated he was either going to take a backseat to allow a fresh lead to be given to the party or that he was prepared to move out of the party leadership.

In every instance in the past when he has spoken of taking a backseat or moving out, he has initiated a two-pronged approach. The first is to put pressure on the other side, in this case the SJB, by making it public that he (Wickremesinghe) is supportive of the alliance and is prepared to even give up the UNP leadership. Through this move, the onus falls on the SJB to act on the statement.

The next move is to get his loyalists in the UNP to publicise Wickremesinghe’s magnanimous nature and to blame the SJB for delaying the process while another group of loyalists, especially two senior party members despised by a majority of UNPers, engage in internal processes to block the SJB from confidently forming the alliance.

Once these actions are put in motion, the SJB, realising that Wickremesinghe is back to his old antics, will become hesitant to align with the UNP, resulting in the former President’s loyalists then making public statements naming the SJB leadership as the truant.

All these moves would result in some SJBers, who are engaged in talks with the UNP and rooting for an alliance between the two parties, becoming disgruntled and Wickremesinghe will then get his loyalists to try and poach these SJBers to the UNP.

It is also no secret that Wickremesinghe, since 2022, has been sympathetic towards some SLPPers with whom the SJB has already expressed displeasure over potentially being aligned with, and is also comfortable working with these SLPPers. Wickremesinghe would work on getting these SLPPers to the UNP fold due to the belief that with the SJB and SLPP defectors, he could once again strengthen the UNP and rule the party for many more years to come.

Being a master in the policy of divide and rule, Wickremesinghe most often acts with an ulterior motive.

Therefore, the statement claimed to have been made by the former President about his preparedness to step down from the party leadership to pave the way for an alliance between the SJB and UNP was not taken seriously by many Opposition politicians, including many UNPers as well.

SLFP makes changes

Meanwhile, the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), which is on a path to unite all divided factions and reform the party, has made significant changes to the party’s Constitution during a special meeting of its Executive Committee and All-Island Working Committee last Sunday (14) at the Party Headquarters on Darley Road in Colombo.

Party Leader, former Minister Nimal Siripala de Silva headed the meeting that was attended by all party seniors and members of the two key decision-making bodies.

Apart from endorsing several new appointments to key party positions, the party Constitution was also subjected to significant changes, which party seniors stated would further strengthen internal party democracy. A senior party member noted that while many political parties had party leaders with excessive powers who had decision-making powers mostly vested with them, the SLFP had decided to reduce the powers vested with the party leader.

Accordingly, the SLFP leader will no longer be vested with the power of removing a party member since such a move would now have to be made with the approval of the Politburo. While the party leader can appoint or remove a member of the party, it will now have to be done with the approval of the Politburo.

The other key change introduced was in relation to the appointment of members to the Politburo. Earlier, it was the party leader who had the power to appoint all 15 members of the SLFP Politburo. However, this has now been changed to permit the party leader to appoint seven members to the Politburo and that too should be done in consultation with the senior office bearers. The remaining eight members of the Politburo will be ex officio members like the general secretary, national organiser, treasurer, etc.

These changes to the party Constitution, it is learnt, are aimed at preventing the party leader from removing or expelling members who oppose the party leadership.

The SLFP has also reduced the minimum age for party membership from 18 years to 16 years.

New appointments

Meanwhile, Opposition MP Chamara Sampath Dasanayake was appointed as the SLFP National Organiser at last Sunday’s meeting.

The decision to appoint Dasanayake as the SLFP National Organiser was made at the party’s Executive Committee meeting held last Sunday (14). He was also appointed as the SLFP’s Parliamentary Leader.

The SLFP has been making appointments to key internal positions as part of the party’s reorganising programmes. Former Minister Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe, who joined the party recently, was also appointed to several key positions.

However, prior to appointing Dasanayake as the SLFP National Organiser, the post was offered to former General Secretary of the SLFP Dayasiri Jayasekara, who is currently in litigation challenging his ouster from the party post.

Dasanayake himself noted that the post of national organiser was first marked for Jayasekara and that he was appointed to the post since Jayasekara had declined it. Dasanayake also claimed that he had been appointed as the party’s Parliamentary Leader since Jayasekara represented the SJB in Parliament.

However, he further noted that he was prepared to move out of the national organiser post and make way for Jayasekara to assume the post if the latter decided to return to the party fold.

Dayasiri hits out

Jayasekeara meanwhile hit out at the meeting of the SLFP’s Executive Committee and the All-Island Working Committee by issuing a letter to SLFP members on an SLFP letterhead signed by him as the general secretary of the party.

Jayasekara has claimed in the letter that the meeting convened by Nimal Siripala de Silva and his group has violated the party Constitution yet again. He has also noted that the Election Commission did not accept the SLFP due to the ongoing legal cases.

Explaining further, Jayasekara has stated that the Election Commission would officially recognise the party only after the conclusion of the ongoing legal cases and upon the commission being informed of the final decision and the party’s stance. Until such time, Jayasekara has said that party members were being misled by one group through temporary moves.

Jayasekara has gone on to point out that the crisis in the SLFP had started when the 14 SLFP MPs in Parliament during the Gotabaya Rajapaksa administration had decided to resign from the Government in May 2022, as well as by nine of the SLFP MPs deciding to join the Ranil Wickremesinghe Government by assuming ministerial positions afterwards.

Referring to the statement made by Dasanayake that he (Jayasekara) was representing the SJB in Parliament, Jayasekara has clarified that he had not joined the SJB and that he had contested after reaching an agreement with the SJB-led alliance that he would contest under the alliance as a member of the SLFP and that SJB General Secretary Ranjith Madduma Bandara had accepted this and informed the Election Commission about it.

Jayasekara has also questioned how Dasanayake could be appointed as the Parliamentary Leader of the SLFP when he was given nominations by the General Secretary of the New Democratic Front (NDF) under the ‘gas cylinder’ symbol and not by the SLFP.

According to Jayasekara, the cases filed by him before the Colombo District Court challenging the allegedly illegal way in which he was removed from the post of party general secretary and the manner in which de Silva had assumed the post of party leader were up for their final verdict on Thursday (18).

Displeasure over changes

It is also learnt that the latest changes being made within the SLFP have not gone down well with some party members, especially the SLFP member who had earlier led the party in the Colombo District.

The SLFP’s Faiszer Musthapha, PC also entered Parliament following the last Presidential Election through the NDF National List while Dasanayake was elected to the House from the Badulla District.

However, it is learnt that Musthapha is currently disgruntled that Rajapakshe has been appointed as the SLFP’s Colombo District Leader while Dasanayake has been appointed as the party’s Parliamentary Leader.

Maithri’s poetry

While the SLFP is travelling on a potholed path towards rebuilding the party following the many breakaways and factions, former Leader of the SLFP and former President Maithripala Sirisena was recently seen reciting a poem at the launch of a book of poetry in Colombo where he was the Chief Guest.

The poetry book contains poems about several former politicians. Former Prime Minister Dinesh Gunawardena had also attended the event.

When invited to address the gathering, Sirisena had gone to the podium and commenced his speech with a poem.

GL’s book

Meanwhile, former Minister G.L. Peiris is set to launch a book written by him – ‘The Sri Lanka Peace Process: An Inside View’ – containing details of the processes launched by several governments during the period of the war.