Emerging market economies and their currencies have come under severe stress in recent weeks, as rising US interest rates and trade fears prompt investors worldwide to shun their assets and move money to the US.

A strengthening American economy, a strong US dollar and growing trade tensions have led to a rout in emerging markets over the past several weeks, as investors are increasingly shifting their money to the US.

Inflows of foreign investment into emerging economies shriveled to $2.2 billion (€1.9 billion) in August, the Institute of International Finance (IIF) said in a report. In July, these markets saw portfolio inflows of $13.7 billion (€11.8 billion).

As the US central bank remains on course to normalize monetary policy, by hiking its benchmark interest rates two more times before the end of this year, financial conditions in other parts of the world appear to have tightened.

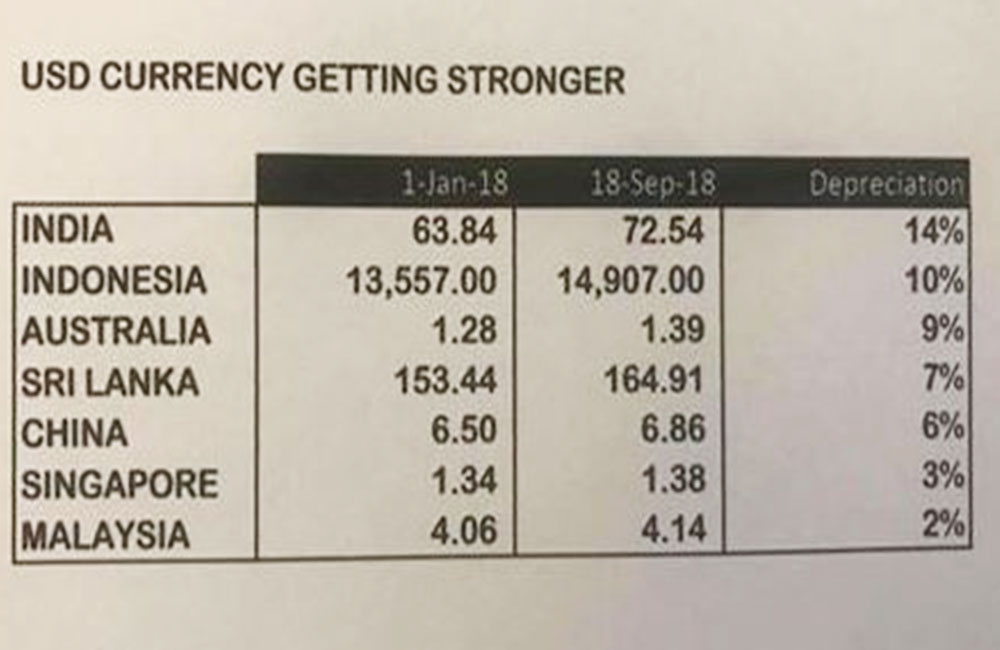

Some Asian countries have been hit hard by the selloff of emerging market assets, with their currencies plunging in value against the US dollar. The situation has stoked fears that Asia is on the verge of facing another financial crisis like the one seen during 1997-98.

The Indonesian rupiah has slumped to its lowest level since the Asian financial crisis in the late nineties. Since the start of the year, the rupiah has been down by 9.2 percent against the greenback.

But the worst performing Asian currency this year has been the Indian rupee, which has lost about 12 percent against the dollar.

Winners and losers

Not all Asian nations have been negatively affected, however. Thailand's currency, the baht, for instance, has remained resilient in the face of the emerging-market rout. Economists say Thailand's large current account surplus and adequate foreign exchange reserves might have cushioned the country's currency from the current turmoil on the markets.

Thailand's current account surplus is expected to be around 9 percent of GDP this year, on top of the double-digit levels in the past two years. The baht's present performance is in stark contrast to its fate in 1997, when it collapsed over 50 percent during the six-month period after the panic set in.

But unlike Thailand, countries like India and Indonesia suffer from high current account deficits. These deficits occur when the value of the goods and services they import exceeds the value of the goods and services they export. This weakens a nation's currency, making them more vulnerable to global market fluctuations.

"Supporting the rupiah is increasingly becoming the central pre-occupation for Bank Indonesia and the government," Gareth Leather, Senior Asia Economist at London-based Capital Economics, said in a research note.

The Southeast Asian nation's central bank has been aggressively intervening in the forex markets to defend the value of the rupiah. In fact, the bank has spent almost 10 percent of its foreign reserves this year to bolster the currency. Indonesia's reserves fell to about $117.9 billion (€101.4 billion) in August, the lowest since January 2017. The reserves are still enough to finance over six months of imports and service the government's external debt, according to the central bank. Nevertheless, the situation has underscored Indonesia's vulnerable financial position.

"The Indonesian economy is facing some structural weaknesses," Rizal Ramli, an Indonesian politician and economist, told DW, pointing to the country's high deficit and debt figures.

The Indonesian rupiah has slumped to its lowest level since the Asian financial crisis in the late nineties

The Indonesian rupiah has slumped to its lowest level since the Asian financial crisis in the late nineties

If the central bank keeps raising interest rates without any support from the government in introducing structural reform measures, it wouldn't be useful in resolving the problem, said Ramli, who served as coordinating minister for maritime affairs under President Joko Widodo administration as well as coordinating minister for economic affairs and minister of finance.

The current way of doing things "will lead to an increase in non-performing loans and credit problems in financial institutions," he stressed.

Problems even for growing economies

Meanwhile, India's current account deficit this year is going to be worse than that of Indonesia, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The IMF estimates the South Asian nation's deficit to be around 2.6 percent of GDP this fiscal year, up from 1.9 percent last year.

India's fiscal deficit is also one of the worst, with the government reporting a deficit of $62.57 billion (€53.85 billion) for the April-June quarter. The nation's economic growth, though, seems to be robust, with GDP expanding by 8.2 percent in the quarter ending June. It also boasts a large foreign exchange reserve, amounting to some $400 billion as of August.

Despite the depreciation in their values, Asian currencies like the rupee and rupiah sit somewhere in the middle of the list of emerging currencies that have been bashed by the markets. They haven't been as resilient as currencies such as the Thai baht; but they have also not been smacked in the same way like the Turkish lira or the Argentine peso.

To support their currencies and curb inflation, officials in some Asian countries have resorted to raising interest rates. The central banks of the Philippines and India have already raised rates by 100 basis points (1 percent) and 50 basis points respectively this year.

Experts believe Indonesia and the Philippines will likely tighten monetary policy aggressively in the coming months, as they both struggle to get a grip over soaring inflation.

Dollars and sense

Still, the recent developments in the global currency markets are unlikely to cause another Asian financial crisis, Charlie Lay, emerging markets analyst at Germany's Commerzbank, told DW.

"The landscape in Asia today is a lot different compared to 1997," Lay said. "Companies have less leverage now and are less exposed to dollar-denominated debt," the expert noted, adding that "improved macroeconomic management, a more flexible exchange rate regime and current account surpluses in most Asian economies" mean that they are less vulnerable today than two decades ago.

Although many countries have made significant progress in modernizing and reforming their financial, labor and product markets, they have fallen short of implementing the deep-rooted structural reforms needed to boost productivity and output growth in the long run.

Furthermore, the deteriorating macroeconomic conditions as a result of increasing protectionist tendencies worldwide could adversely affect them, say observers. That's particularly the case for economies in Southeast and East Asia, which are heavily reliant on global trade flows for their prosperity.

"The best way for Asia to prepare against a further spike in volatility and ructions in the financial markets is to ensure sound economic management, including preventing excessive leverage, ensuring fiscal discipline and allowing exchange rate flexibility," said Lay.

By Srinivas Mazumdaru via DW.com. Additional reporting by Yusuf Pamuncak.

Leave your comments

Login to post a comment

Post comment as a guest